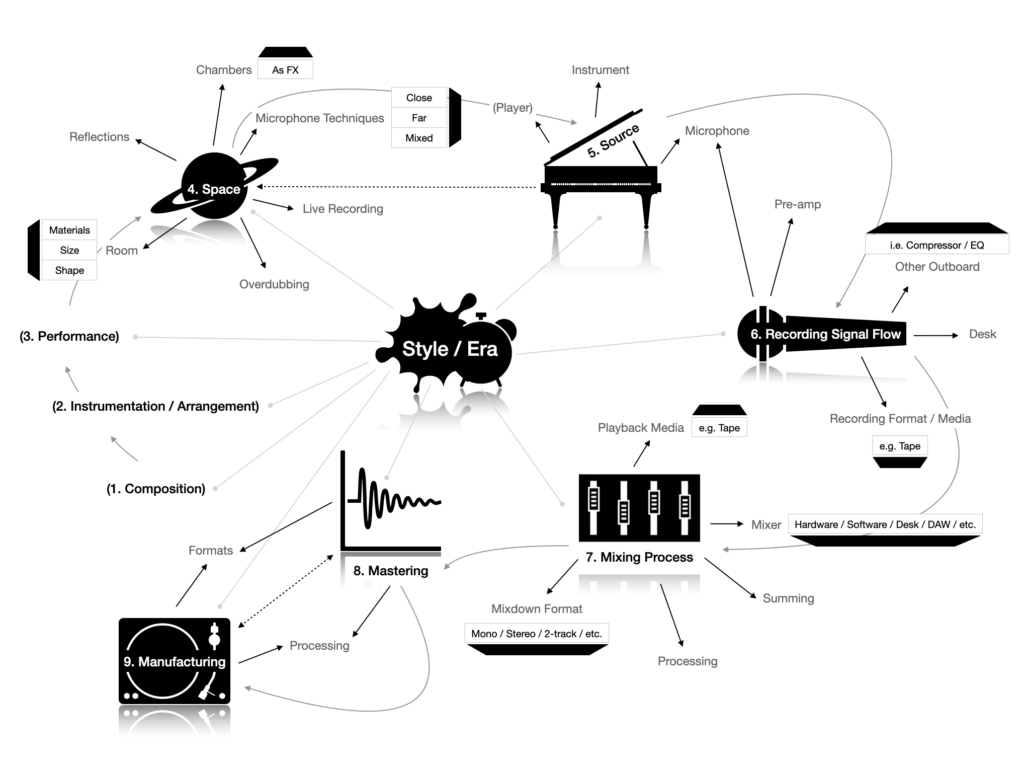

Following on from the ‘phonographic other’ earlier post, I want to expand somewhat on the concept, discuss relevant metaphors and attempt to define a typology of variables contributing to a phonographic ‘otherness’, as it features in sample-based hip-hop.

Going beyond how I originally perceived and explained this sonic otherness, I now want to focus on its implications in the context of (sources) being featured within new phonographic constructs. It becomes an issue of consciously featured phonographic contrast, which is a key aesthetic delineator of the boom-bap (sample-based hip-hop) sound. What’s more, I believe that existing literature has dealt rather extensively with the musical (motivic) aspects of what exemplifies otherness within a new music production: the re-imagined phrases resulting from ‘chopping’ (Williams, 2014), the rhythmical and musical (harmonic-melodic) interactions audible as a result (Schloss, 2014), even the dissonance described in Krims’s (2000) ‘hip-hop sublime’. And although Krims goes as far as to include timbral implications of such layering in his definition of the ‘sublime’—and Sewer (2013) provides an extensive typology of layering in earlier sample-based Hip Hop—very little analysis focuses in on the mix-architectural aspects of this otherness; in other words, the mechanics of the layering (how does it work from a mix perspective), or the sonic makeup/DNA of this defining sonic signature for the (sub)genre.

So, here I will attempt a typology of perceivable characteristics—from a mix-architecture perspective—that define this featured, phonographic otherness. Furthermore, I will highlight characteristics delineating contrast between sources featured and other beat-making elements, and finally I will include sonic characteristics key to how this otherness is integrated back into the sample-based hip-hop phonographic construct.

Sample characteristics defining featured ‘otherness’

- – Limitations in source’s frequency range

- – Recording signal path colourations (sound of the mixing desk, recording medium, any outboard, microphones)

- – Mixing signal path colourations (sound of the mixing desk again, recording medium in playback mode and shared outboard)

- – End format/medium/master sound (colouration, distortion) [e.g. master tape/vinyl]

- – Shared captured spaces over recorded elements (original rooms, echo chambers)

- – Shared spaces applied in the mix/post-production

- – Playback devices/formats used to record samples (vinyl player, DJ mixer, Youtube/Spotify codec)

- – Sampling devices/formats used to record, manipulate and play back samples (phono inputs on MPC sampler, digital extraction codec, virtual software sampler algorithm, filtering, pitch shifting*)

- – Surface noise resulting from various mechanical/magnetic production phases

- – Staging architecture achieved as a result of mixing decision on three axes/dimensions (stereo width: X – frequency height: Y – depth: Z)

- – Mix-buss processing, and colouration when hardware is used (shared EQ, dynamic processing, stereo enhancement, sound of outboard)

- – Mastering processing, and colouration when hardware is used (shared EQ, dynamic processing, stereo enhancement, sound of outboard)

- – Purposeful accentuation of source lo-fi-ness (quality/resolution reduction, increase of surface noise)

- – {Musical: harmonic, melodic, rhythmic, stylistic coherence

- – Structural: cuts, looping/repetition}

* when filtering, pitch-shifting or manipulating a source as one, global processing ties the included/featured elements/instruments arguably further together…

Characteristics delineating contrast

- All of the above, plus…

- – Live source vs. programmed beat (rhythm)

- – Acoustic and/or electromechanical vs. synthetic (timbre)

- – Spatial decay or glue over source elements vs. Individual/single/gated hits of beat production (spatial)

- – Analogue vs. digital colourations

- – Physical sound that has manifested as molecule vibrations vs. DI’d

Characteristics representative of ‘integration’ back into the beat

- – Sampler, DAW, music production environment outputs/algorithm/resolution characteristics

- – Recording signal path colourations (sound of mixing desk, recording medium, any outboard)

- – Mixing signal path colourations (sound of mixing desk, recording medium in playback mode and shared outboard)

- – End format/medium/master sound (colouration, distortion) [e.g. master tape/vinyl]

- – Shared captured spaces over recorded elements (original rooms, echo chambers)

- – Shared spaces applied in the mix/post-production

- – Staging architecture achieved as a result of mixing decision on three axes/dimensions (stereo width: X – frequency height: Y – depth: Z)

- – Mix-buss processing, and colouration when hardware is used (shared EQ, dynamic processing, stereo enhancement, sound of outboard)

- – Mastering processing, and colouration when hardware is used (shared EQ, dynamic processing, stereo enhancement, sound of outboard)

- – {Musical & structural integration (jamming with source, rhythmical interactions, complimentary layering/chopping)}

See, simply making a record is conceptually different to making a record that will feel ‘other’ within another record(-making process). This is why this process of trying to make convincing phonographic ‘others’ (making records within records) feels of important educational value. It is one thing to (aurally) analyse discography illustrating the phenomenon from a surface level (I think this is why most scholars stop at a motivic—and some surface timbral descriptions of an—analysis), and it is another attempting to construct it intrinsically. This process provides a rich opportunity for detailed, complex, personal accounts of the effort , and consequently an arrival at defining variables of the process that lead to the phenomenon (or a successful replication of the sample-based aesthetic by the contemporary ‘re/constructionists’).

References

Krims, A. (2000) Rap music and the poetics of identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schloss, J.G. (2014) Making beats: The art of sample-based Hip-Hop. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press (Music/culture).

Sewell, A. (2013) A Typology of Sampling in Hip-Hop. Unpublished PhD thesis. Indiana University.

Williams, J.A. (2014) Rhymin’ and stealin’: Musical borrowing in Hip-Hop. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Williams, J.A. (2014) ‘Theoretical approaches to quotation in hip-hop recordings’, Contemporary Music Review, 33(2), pp. 188–209.